Bow Legs

Humans have a keen eye for what is normal or abnormal. The great artist and philosopher Leonardo da Vinci’s sketch of the Vitruvian man shows us the perfect geometric proportions of a human body. An understanding of lower limb alignment must first start by knowing what is the normal lower limb mechanical alignment.

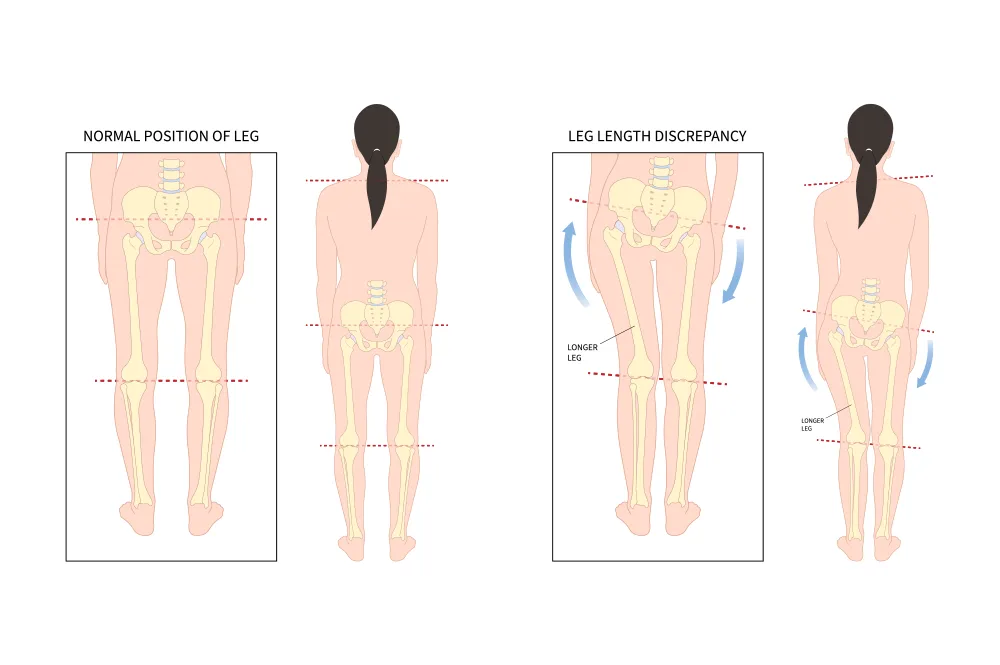

In the standing position, a person’s body weight passes from the centre of the hips down through the centre of the ankles. In a normal individual, this line should pass through the knee almost at the midline. This is known as the mechanical axis.

What does being “Bow-legged” mean?

Bow-legged refers to the observation (when viewed from the front) that there is a gap between a person’s knees when he/she is positioning the limbs alongside each other. The medical term for this is genu varum. If the mechanical axis lines are drawn, they will pass through the knee on the inner side of the knees.

How do I tell if my child has bow legs?

While standing, position his/her legs side by side. Try to do this with the knee caps pointing forwards, and make sure that his/her pelvis is not tilting to one side. If the right and left ankles touch each other before the knees touch each other, and there is a visible gap between the knees, your child may have bow legs. An assessment by your GP, paediatrician, or paediatric orthopaedics doctor can determine if this bowing is significant or not.

So, what is the problem with bow legs?

The main issue with bow legs is the abnormal concentration of weight and loading forces on the inner (medial) aspect of the knee. Over time, this will lead to cartilage and meniscus injuries, and degenerative osteoarthritis of the medial compartment of the knee.

Is bow leggedness always abnormal?

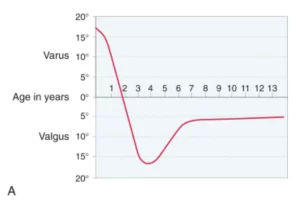

Interestingly enough, almost all babies are born with bowed legs. This was observed by a Finnish doctor, Dr. Salenius, who studied the natural history of 1480 children. While in the womb, most babies have their lower limbs flexed at the hips and knees, with internal rotation of the tibia and feet. This causes tightness of the medial knee capsule. Depending on how soon this tightness stretches out, varying amounts of bow-leggedness will still be visible when children first start walking.

In this chart documented by Dr. Salenius and the team, children are born with the maximum magnitude of bowed legs (varus). This gradually improves until the age of 1 to 22 months. After which, lower limb alignment then swings into valgus (or knock-knees). The worst magnitude of knock knees is seen around 3 to 4 years old. From there, the valgus knee alignment improves until about 6 to 8 years old, when most children achieve the adult lower limb alignment position.

In simple terms, what this chart tells us is that bow-leggedness is usually normal if the child is less than 2 years of age. After the age of 2 years, persistent bow-leggedness should be investigated for pathologic causes.

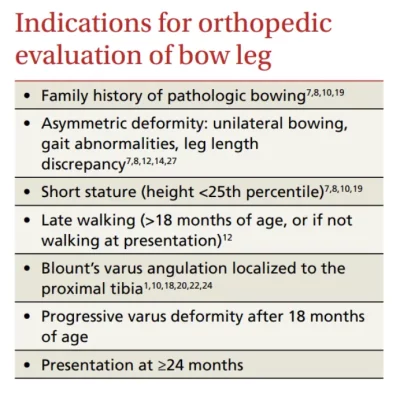

When should I get worried?

If the child’s leg alignment falls outside of the expected curves described by Dr. Salenius. This means that if the bow legs are still present after 2 years of age, further investigations should be carried out. Other indications that may warrant a specialist opinion include the following, as suggested by Dettling et al.

What is the cause of bow-leggedness?

- I. Physiologic

- II. Pathologic

- Blount’s disease

- Hypophosphatemic or nutritional rickets

- Post traumatic

- Post infections

- Congenital deformities

- Dysplasias focal fibrocartilaginous dysplasia metaphyseal chondrodysplasia Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia / Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia

- Fibrous dysplasia

- Osteogenesis imperfecta

- Renal osteodystrophy

My approach:

When I am presented with a child with bow-leggedness, some important questions that will help with assessment include the age and growth percentiles of the child. It is important to identify if the bow legs are physiological, or pathological. As you know, below the age of 2 years, bow-leggedness is usually physiological. This means that they are expected to improve spontaneously over time. The height and weight percentiles are also important. Children who have Blount’s disease are usually growing much faster than their peers (i.e. > 90th percentile in height and weight). Children with rickets or skeletal dysplasias, on the other hand, are usually shorter and smaller.

Depending on the suspicion of the possible diagnoses, various tests may be conducted. A standing lower limb X-ray, usually in the form of an EOS X-ray, is an advanced X-ray imaging technique that has markedly reduced (8-40X less) radiation when compared to traditional X-rays. These EOS X-rays can determine the severity of the bow-leggedness. This is usually quantified by how far the mechanical axis passes the medial to (inside of) the middle of the knee. The quality of the growth plates, epiphyseal, and metaphyseal development can also give clues to the underlying pathology. A bone age X-ray of the left hand may also be taken to determine the estimated bone age.

Metabolic profile tests like blood calcium, phosphate, and Vitamin D levels will be ordered. Treatment of bow legs is dependent on the underlying cause.

Bow Leg Correction

How do I treat bow legs?

The treatment will depend on the underlying cause. Physiological bow legs will resolve spontaneously, and no further treatment is usually needed. Certain metabolic conditions like rickets need to be treated with medications like Vitamin D or phosphate replacements.

For skeletally immature children (before their bones stop growing), we can use a small surgical technique known as growth modulation (or hemiepiphyseodesis). This involves surgically positioning a plate (it is often called an 8-plate due to the shape of the plate) and 2 screws across the growth plate. This creates an inhibition on the growth on that side of the growth plate, while the other side of the knee continues to grow. Over time, the legs will straighten out.

For skeletally mature children (after their bones have stopped growing), or if their bone age is more than 12.5 (for girls) and 14.5 (for boys), a larger surgical operation known as a corrective osteotomy will need to be performed. This involves making a precise cut in the bone, acutely correcting the deformity, and positioning a locking plate and screws to hold the new bone position.

In some children, their deformities are more complex (in more than one plane), or they may also have significant shortening of the bowed leg. These cases will need gradual correction with the use of an external fixator.

References:

- Salenius P, Vankka E. The development of the tibiofemoral angle in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57:259-261.

- Weiner DS. The natural history of “bow legs” and “knock knees” in childhood. Orthopedics. 1981;4:156-160

- Dettling S, Weiner DS. Management of bow legs in children: A primary care protocol. J Fam Pract 2017 May;66(5):E1-E6

Media spotight

Dr Lam Kai Yet

Dr Lam is an experienced and accomplished paediatric orthopaedic surgeon who is actively involved in research in paediatric trauma, limb lengthening, and deformity correction, sports injuries, and 3D-printing.

He is dedicated to bringing a new level of expertise and care to the emerging field of paediatrics orthopaedics in Singapore. He has amassed experience in this specialised field, through his practice in KKH, as well as overseas fellowships, specialised trainings, and conferences.

He believes that care should be tailored to one’s individual and unique needs.