Paediatric Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injuries

Paediatric ACL injuries are on the rise due to an increase in the level and number of organized sports amongst children. This injury can be devastating, and career-ending even for some athletes: https://www.theguardian.com/football/blog/2014/nov/15/adrian-doherty-manchester-united-class-of-92

Yet due to recent advances in medical science, especially in ACL reconstructive surgery, there have been several success stories, where world-class athletes can still compete at the highest levels: https://www.givemesport.com/1609268-virgil-van-dijk-9-worldclass-players-who-suffered-acl-injuries-including-ibrahimovic-xavi-and-keane

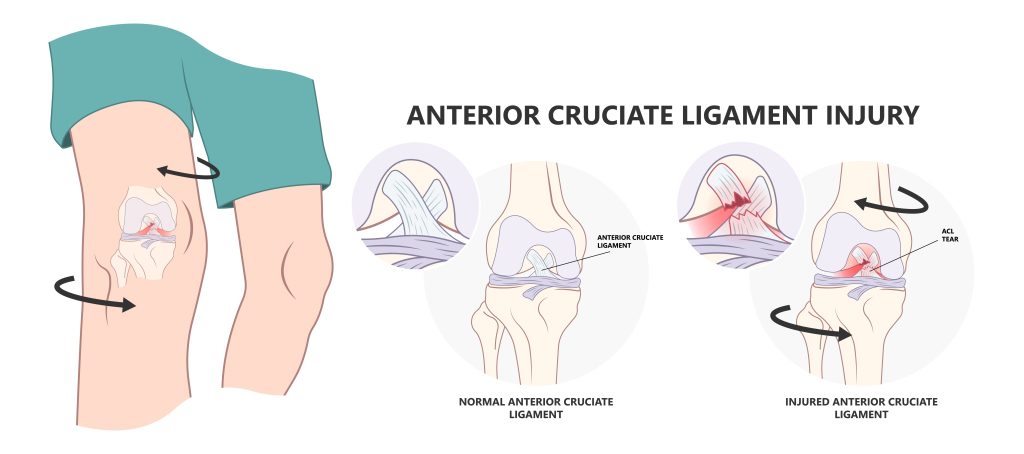

What is an ACL injury?

ACL injuries refer to complete or partial tears in the substance of the ACL. This usually happens after a twisting injury in the knee. The patient will usually have significant pain and swelling in the knee, and they may have heard a ‘pop’ or ‘crack’ sound during the accident. Physical examination will usually show a swollen knee, stiffness and the knee will be unstable on stress testing (Lachman’s test or anterior drawer test). The swelling and pain will usually subside after a few weeks, but the child will still experience a loose knee, or buckling of the knee, especially when he/she tries to change direction or pivot quickly.

Is there a difference between Paediatric and Adult ACL ligament injuries?

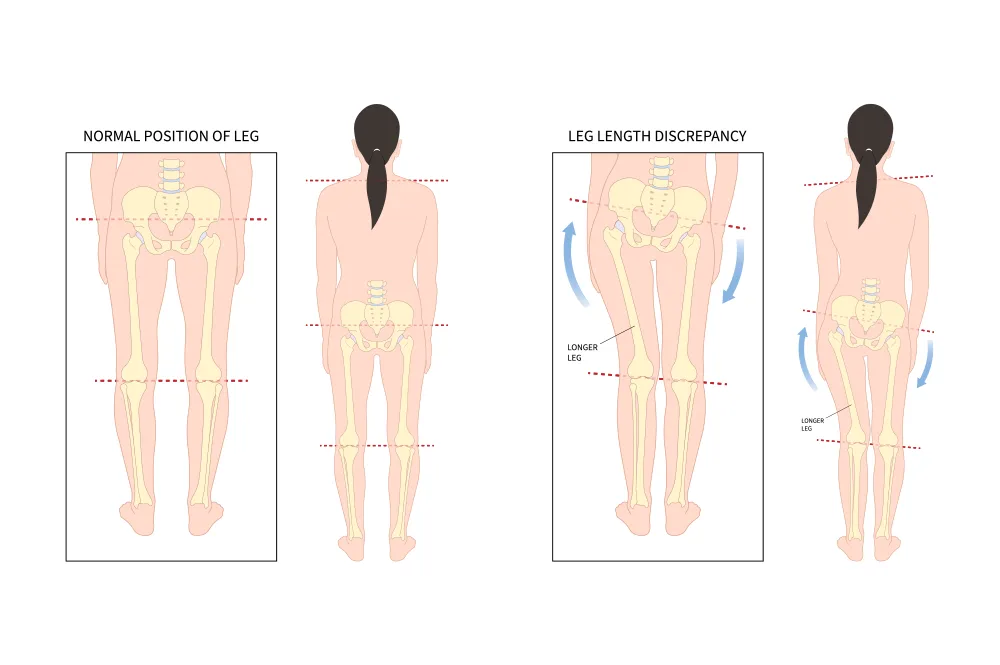

Yes! Paediatric patients are inherently different from adults in several ways. Anatomically, the femoral notch is smaller (meaning there is less space), and there are growth plates (where the bones grow!) around the knee. The growth plates around the knee contribute to most of the growth of the lower limb, meaning that any surgical procedures performed can result in growth disturbances like leg malignment or limb shortening. The high activity level in children also mean that they are prone to repeated twisting injuries in their knees throughout their childhood.

In children, due to the relative weakness of bone compared to the ligaments, it is important for the attending physician to first exclude other injuries like the ACL tibia spine avulsion fracture, patella sleeve fracture or tibia tuberosity fractures (which are quite unique to the paediatric population).

Is there a role for non-operative management?

In 1988, a study published in the American Journal of Sports Medicine by McCarroll followed up 16 children with ACL injuries that were treated non operatively. At 2.5 years follow-up, 100% of the patients had recurrent instability, while only 43% returned to sports. Concurrently, of 24 children who had an ACL reconstruction, 92% returned to sports. [1] This study was supported by Mizuta et al in 1995 where only 1 of 18 patients treated non operatively returned to sports at the same level, and 89% of them had fair or poor functional results. [2] Subsequent systematic reviews and meta-analyses [3][4] showed that patients treated non operatively continued to suffer from knee instability, further meniscus and cartilage damage. Their conclusion was that conservative (or non-operative) treatment should be reserved for only the compliant patients who have a low physical activity level. The PLUTO (Pediatric ACL: Understanding Treatment Options) study group also agrees that “nonoperative management of ACL injuries resulted in a high incidence of secondary meniscal pathology, persistent knee instability and low rates of return to sports”.

Any parent will tell you the compliant patient who has a low physical activity level is almost non-existent! This group of patients (if they exist) would probably not be the typical child who suffers an ACL injury anyway.

Can I delay my operation?

In the past, ACL reconstruction surgeries have been delayed till skeletal maturity (when the child stops growing). The main rationale for this is that there is potential damage from the ACL reconstruction on an open growth plate. Possible complications from surgery would be limb malalignment (genu valgus or tibia recurvatum) or limb shortening. If the child has more than 1 year of growth remaining, these complications are a real consideration. However, recent advances in surgical techniques have reduced the chances of these complications without compromising on knee stability at final follow-up [7][8].

Conversely, the medical literature is quite consistent in showing that there is increased risk of meniscal tears (increased 4.3X), and irreparable meniscus tears (increased 3.2X) if the ACL reconstruction is delayed by more than 12 weeks from the date of injury [5].

In short, the answer to this question is that you should not delay the operation. Of course, any decision for surgery, and timing of surgery should be catered to the individual, and be discussed in detail with your attending surgeon.

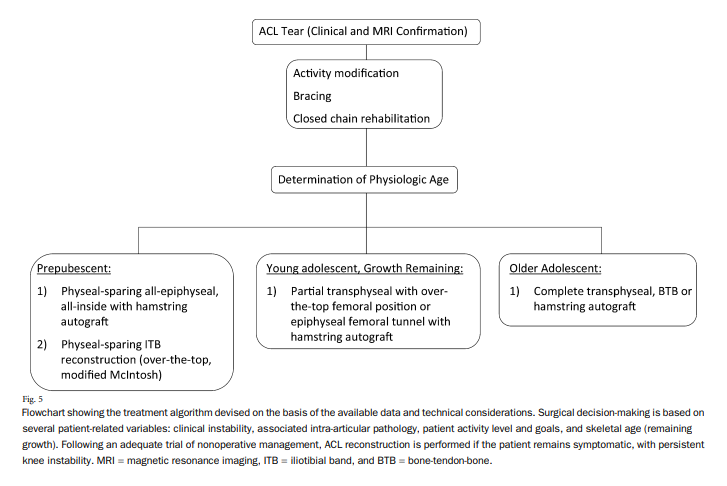

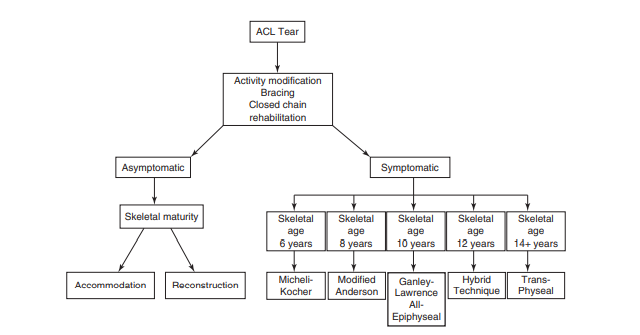

Paediatric ACL Treatment Algorithms

There are several treatment algorithms for paediatric ACL injuries, but they all follow a similar format. The main aim of assessment is to determine how much potential growth a child has at the time of the ACL injury, and to select a surgical technique that is appropriate, with the least possibility of damage to the growth plates, yet offering the most amount of stability.

Treatment Algorithm from Hospital of Special Surgery, New York [9]

Treatment Algorithm from Dr Milewski [10]

How to Determine Skeletal Maturity and Growth remaining?

This is assessed via a radiological and a physiological assessment. An X-ray of the left wrist and hand is usually ordered by the attending doctor. This X-ray is then compared against the Greulich and Pyle atlas, which remains the gold-standard for skeletal bone age assessment. This atlas was compiled from thousands of X-rays from young children in Ohio in the 1950s. Other atlases and measurement tools have since been described (Tanner and Whitehouse method, HSS shorthand tool, Knee Pyle and Hoerr atlas), but these have not been as well validated. Physiological assessments via the Tanner staging and the onset of menarche in girls can also be a useful estimate.

Based on the skeletal bone age assessment, we can determine the amount of growth remaining in the child based on the charts derived by the French professor, Alain Dimeglio.

My Approach

After my clinic assessment, and determination of the skeletal maturity, and growth remaining of the child, I will usually streamline him/her into one of two groups.

a. Pre-Pubescent (>5cm Growth left)

These patients are at high risk of growth disturbances if the growth plate is damaged during surgery. Special techniques like the All-epiphyseal, all-inside (if the epiphysis is large enough) or the Micheli-Kocher techniques are my preferred techniques for these patients.

b. Young adolescent (1-5cm growth left) or Older adolescent (<1cm growth left)

These patients can be safely treated with a transphyseal ACL reconstruction like those used in adult ACL reconstructions. However, special precautions still need to be taken to avoid any potential complications from the femoral and tibial tunnels. Kocher et al. had shown.

With this, we can choose the safest and most appropriate paediatric ACL reconstruction technique for the patient.

This article was presented by Dr Lam Kai Yet at the Singapore Orthopaedic Association Annual Scientific Meeting on 8 Dec 2022, as an invited faculty.

References

- McCarroll JR, Rettig AC, Shelbourne KD. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in the young athlete with open physes. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16:44-47.

- Mizuta H, Kubota K, Shiraishi M, et al. The conservative treatment of complete tears of the anterior cruciate ligament in skeletally immature patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:890-894

- Moksnes H, Engebretsen L, Risberg MA. Prevalence and incidence of new meniscus and cartilage injuries after a nonoperative treatment algorithm for ACL tears in skeletally immature children: a prospective MRI study. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:1771-1779.

- Vavken P, Murray MM. Treating anterior cruciate ligament tears in skeletally mature patients. Arthroscopy 2011;27:704-716.

- EW James, BJ Dawkins, JM Schachne et al. Early operative versus delayed operative versus nonoperative treatment of pediatric and adolescent anterior cruciate ligament injuries. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 2021;

- Pediatric ACL: Understanding Treatment Options (PLUTO). US National Library of Medicine Clinical Trials. First posted May 16, 2016. Last update posted Sept 21, 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02772770

- Anderson AF. Transepiphyseal replacement of the anterior cruciate ligament using quadruple hamstring grafts in skeletally immature patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(Pt2)(Suppl 1):201-9

- Lawrence JT, Bowers AL, Belding J, Cody SR, Ganley TJ. All epiphyseal anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in skeletally immature patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010 Jul;468(7):1971-7.

- Fabricant PD, Jones KJ, Delos D, Cordasco FA, Marx RG, Pearle AD, Warren RF, DW Green. Reconstruction of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament in the Skeletally Immature Athlete: A Review of Current Concepts. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95:e28(1-13)

- Milewskii MD, Beck NA, Lawrence JT, Ganley TJ. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the young athlete: a treatment algorithm for the skeletally immature. Clin Sports Med. 2011;30:801-10.

- Kocher MS, Smith JT, Zoric JB, et al. Transphyseal anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in skeletally immature pubescent adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(12):2632–9

Related Video

Dr Lam Kai Yet

Dr Lam is an experienced and accomplished paediatric orthopaedic surgeon who is actively involved in research in paediatric trauma, limb lengthening, and deformity correction, sports injuries, and 3D-printing.

He is dedicated to bringing a new level of expertise and care to the emerging field of paediatrics orthopaedics in Singapore. He has amassed experience in this specialised field, through his practice in KKH, as well as overseas fellowships, specialised trainings, and conferences.

He believes that care should be tailored to one’s individual and unique needs.